By: Disability Rights New York

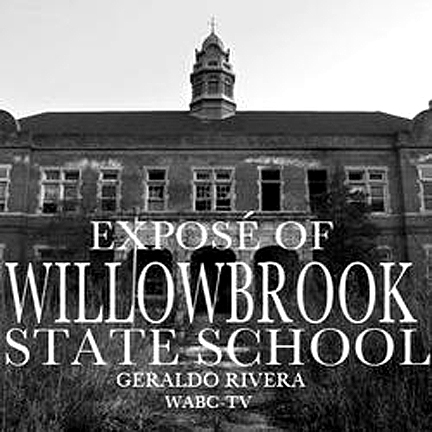

_-_cropped.jpeg) The Willowbrook State School came to be known as a place of abuse, overcrowding, and neglect primarily because of a 1973 public expose’ by Geraldo Rivera. Established in 1947, Willowbrook was a state-operated institution on Staten Island for the care of children and adults with developmental disabilities. By 1969, over 6,000 people were confined to a facility built to serve 4,000. Overcrowding, along with staff shortages and underfunding, led to abhorrent and inhumane living conditions. People were found naked and unattended in filthy conditions, victimized by physical abuse and neglect, and without programming. Following the Rivera documentary, a successful class action was brought on behalf of all Willowbrook residents, and the facility was finally decommissioned in 1987. While Willowbrook was the largest institution for people with disabilities, nearly all states operated similar facilities. In the half-century since the public saw the horrifying images, a raft of legislation creating civil rights and entitlements for people with disabilities evolved, along with legal advocacy organizations committed to enforcing and advancing the rights of people with disabilities. Still, much work remains to overcome substantial barriers to full participation of people with disabilities in all aspects of daily life.

The Willowbrook State School came to be known as a place of abuse, overcrowding, and neglect primarily because of a 1973 public expose’ by Geraldo Rivera. Established in 1947, Willowbrook was a state-operated institution on Staten Island for the care of children and adults with developmental disabilities. By 1969, over 6,000 people were confined to a facility built to serve 4,000. Overcrowding, along with staff shortages and underfunding, led to abhorrent and inhumane living conditions. People were found naked and unattended in filthy conditions, victimized by physical abuse and neglect, and without programming. Following the Rivera documentary, a successful class action was brought on behalf of all Willowbrook residents, and the facility was finally decommissioned in 1987. While Willowbrook was the largest institution for people with disabilities, nearly all states operated similar facilities. In the half-century since the public saw the horrifying images, a raft of legislation creating civil rights and entitlements for people with disabilities evolved, along with legal advocacy organizations committed to enforcing and advancing the rights of people with disabilities. Still, much work remains to overcome substantial barriers to full participation of people with disabilities in all aspects of daily life.

Certainly, a legacy of Willowbrook is the adoption of a community integration model in New York State. The community integration model favors programming and supports of people with disabilities within a community setting verses a large institution. Now, fifty years after the Willowbrook exposé and despite the growth of community integration, we still face some of the same challenges. People remain segregated or at risk of being segregated because of a lack of investment in what is needed for successful inclusion. If the challenge of the last fifty years was ensuring that people with disabilities were not abused in the shadows of segregation, our next challenge must be recognizing how our ableism and discriminatory beliefs prevent people with disabilities from full participation. Our laws may prescribe that people with disabilities not be excluded from participating because of their disabilities, but, in fact, many people with disabilities remain on the outside looking in.

Our educational laws direct that a student with a disability be given the opportunity to attend school with peers without disabilities. Yet, schools consistently fail to provide the staffing, behavioral supports, class sizes, assistive technology, and other resources essential to successful integrated classrooms. As a result, students with disabilities struggle to make meaningful educational progress and are disproportionately removed from classrooms or disciplined; black and brown students with disabilities fare even worse. However, research demonstrates that integration of students with disabilities leads to better educational outcomes for all students, while segregation leads to worse educational outcomes for students with disabilities.

People with disabilities remain unemployed and underemployed. Anti-discrimination laws have not addressed this problem. A 2019 report by the American with Disabilities Act National Network revealed that candidates who disclosed their disability on job applications were 26% less likely to receive expressions of interest from potential employers than were other candidates. Another study published in the Harvard Business Review in December 2017 showed that one-third of respondents said they felt “underestimated, insulted, excluded, or had co-workers feel uncomfortable because of their disability”.

People with disabilities also face enormous challenges living in the community. Finding inclusive, accessible housing is a major challenge for many. The 2021 Fair Housing Trends Report put out by the National Fair Housing Alliance states that “complaints by persons with disabilities account for the majority of complaints filed with FHO’s, HUD, and FHAP agencies.” The report also notes that a primary complaint of people with disabilities is an overt denial of a request for a reasonable accommodation or modification to the housing unit. The supports and services many rely upon to live in the community, including community habilitation, home health-aides and personal care attendants, are constantly underfunded and plagued by staff shortages. The Covid-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these issues, leaving people languishing in homeless shelters and institutional facilities.

People with disabilities also face enormous challenges living in the community. Finding inclusive, accessible housing is a major challenge for many. The 2021 Fair Housing Trends Report put out by the National Fair Housing Alliance states that “complaints by persons with disabilities account for the majority of complaints filed with FHO’s, HUD, and FHAP agencies.” The report also notes that a primary complaint of people with disabilities is an overt denial of a request for a reasonable accommodation or modification to the housing unit. The supports and services many rely upon to live in the community, including community habilitation, home health-aides and personal care attendants, are constantly underfunded and plagued by staff shortages. The Covid-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these issues, leaving people languishing in homeless shelters and institutional facilities.

Guardianship is yet another issue where, despite all the gains that have been made, people with disabilities continue to have to fight for the right to self-determination. The recent public outcry spearheaded by the “Free Britney” movement exposed the insidious nature of guardianship. Like Rivera’s Willowbrook exposé, it was only when the world was willing to really look at the de-humanizing treatment of people with disabilities that change was demanded. Neither fame nor fortune is enough to protect against the heavy-handed use of guardianship.

In spite of the very real progress which has been made since 1973, the physical walls of institutions like Willowbrook have often given way to other barriers to a fully inclusive society. A willingness to seek out, hear, and see people with disabilities and their life experiences is fundamental to change. Vigilant and persistent advocacy to enforce and advance the rights of people with disabilities is likewise essential. Indeed, as a result of the Willowbrook exposé, Congress established the Protection and Advocacy System for people with disabilities in every state and territory of the United States. These federally-funded and independent organizations, along with dedicated and generous supporters such as the Barbara and Gerald S. Hartman Foundation, fiercely fight to bring about the changes in policy, practices, funding, and attitudes to build an infrastructure essential to community integration and a society that is institution-free – with or without walls.

In spite of the very real progress which has been made since 1973, the physical walls of institutions like Willowbrook have often given way to other barriers to a fully inclusive society. A willingness to seek out, hear, and see people with disabilities and their life experiences is fundamental to change. Vigilant and persistent advocacy to enforce and advance the rights of people with disabilities is likewise essential. Indeed, as a result of the Willowbrook exposé, Congress established the Protection and Advocacy System for people with disabilities in every state and territory of the United States. These federally-funded and independent organizations, along with dedicated and generous supporters such as the Barbara and Gerald S. Hartman Foundation, fiercely fight to bring about the changes in policy, practices, funding, and attitudes to build an infrastructure essential to community integration and a society that is institution-free – with or without walls.